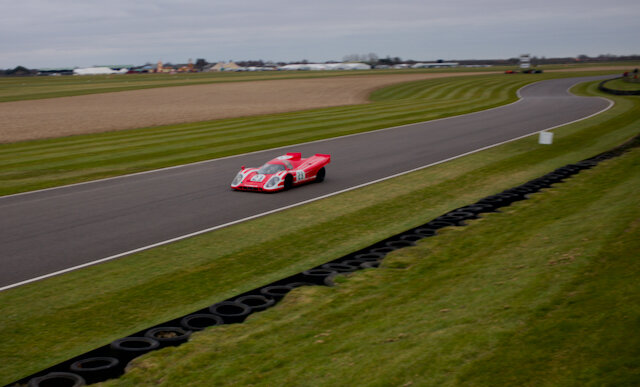

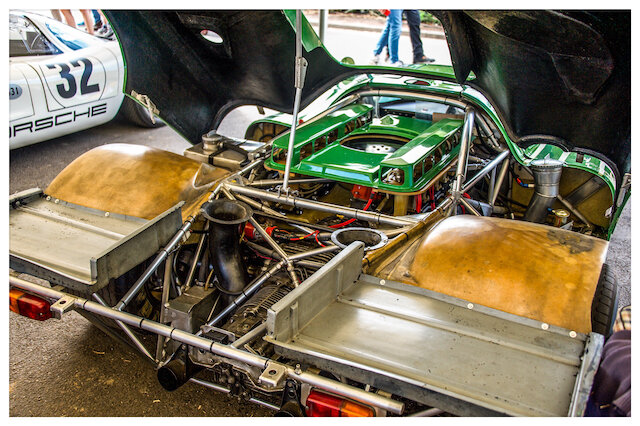

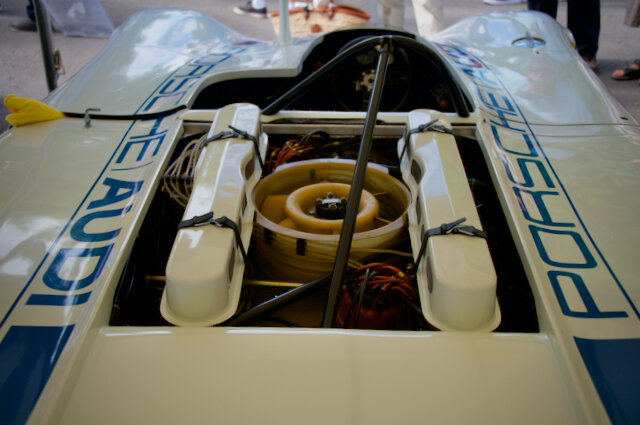

The Porsche 917 was designed under the leadership of legendary Porsche engineer Hans Mezger who recently died at the age of 90 (RIP). Whilst he was involved in many aspects of the Porsche race and production car programme over more than 35 years, the 917 is perhaps his most iconic achievement. Like a number of manufacturers in the 1950s and 60s Porsche had ambitions to win at Le Mans. By the mid-60s Ford and Ferrari were dominating in the battle to win there with hugely advanced, powerful cars that Porsche found it difficult to match. Their cars were nimble and handled well, but under-powered at Le Mans with the importance of outright speed on the long Mulsanne straight. Rule changes in the late 1960s, which reduced the required number of cars to be homologated to 25, finally gave Porsche the chance to compete. The target class was Group 4 for 5-litre sports cars, which would require a significant new engine design of a size in which Porsche had not previously had experience. The aim was to design and build the car within a very short 10 month time frame, ready for the 1969 race. The structure of the car was to be based on the 908 but using more advanced materials and construction. Reputedly the Porsche Motorsport Team totally miscalculated the time needed to complete the 25 required homologation examples. They fooled the inspectors by fitting some with wooden brake calipers, some hastily glued-on parts and some even had fake engines. Fortunately none of the inspectors took up Ferdinand Piëch’s offer to test drive the cars. The engine design was a massive 5-litre flat V12, which was air-cooled in line with Volkswagen’s conditions for providing a substantial portion of the cars funding. Cooling was achieved using a huge fan to suck air down in to the engine. The first cars were what became known as ‘Langheck’ or ‘Long-tail’ versions and terrified their factory drivers with their high speed handling, some regarding them as “rolling coffins”. David Piper was one of the drivers who played a key role in the development of the Porsche 917, driving it at its debut at the Nürburgring 1,000km in 1969 and to its first international victory with Dickie Attwood at the Kyalami 9 Hour race. In an interview about his early experience with the car, he is quoted as saying: “The 917 was a dreadful thing when I first drove it, virtually undriveable. Porsche asked me to race it at the Nurburgring. None of their test drivers were prepared to give it a go, and they asked me if I knew anyone else who would share with me. So I got hold of Frank Gardner; he said he was up for it, so off we went to Germany. Early on the first morning it was foggy and wet and there was this white car neither of us had seen before, the first Porsche 917. So I hopped in and set off into the Nordschleife. Unfortunately I didn’t put my ear plugs in and the noise from that air-cooled flat-12 was excruciating, because two of the exhaust pipes came out underneath the doors. It had tremendous power but it was difficult to keep it on the road – it was wandering all over the place like a Volkswagen – and the brakes weren’t very good either, plus you were virtually lying flat on your back with your chin on your chest. It squatted down on its back wheels and it went from negative to positive camber the faster you went, so once you started going quickly it was undriveable. I told Frank to be very careful and he came in after one lap and said ‘Jesus, if we go off round here they’ll need a compass to find us!’”. Piper went on to say that “it was a very good car once it was sorted out.” The 1969 24 Heures du Mans is probably a race Porsche would rather forget. None of the works drivers would yet drive the car given their early experience and one of the three cars entered crashed, killing its British driver. The other two 917s entered did lead the race for short periods, but both retired before the full distance of the race. Porsche continued to develop the car to improve its handing, but did not enter a works team at Le Mans in 1970, leaving it to private entrants. One of the principal changes made to the car was the development of the K (for ‘Kurzheck’ or ‘Short-tail’) version, which radically improved its handling. The private teams running in the 1970 race included both LH and K versions and finally the 917K driven by Hans Hermann and ‘Dickie’ Attwood claimed victory for a Porsche, beating the LH version run by the Martini team. Many of the original LH versions were converted in to Ks and a number of totally new K versions were also built, but the LH version was also developed further to improve its stability and handling. So by the time of the 1971 race at Le Mans there were again a mix of new LH and K versions entered. The most advanced of the cars on the grid was a K version built on a magnesium structure and entered by the Martini team. Whilst it turned out to be a bit slower than the latest ‘Long-tail’ cars racing in the JWA Gulf livery, both the LH versions retired leaving the field clear for the Martini car to win. After the 1971 victory the 917s were made redundant for Group 4 racing by rule changes, but rather than abandon them totally, Porsche looked to develop the car further for CanAm racing. They had already started their involvement in CanAm with the 917/10. This again proved highly successful. Initially it became clear that to be competitive much more power was required for the Porsches and so turbo-charging became the favoured solution. Putting out some 950bhp the 1972 turbo-charged cars won the CanAm championship beating the previously dominant McLarens. One last version of the car, the 917/30, was developed with power increased to some 1,100bhp from a 5.4 litre engine sitting in a longer and more aerodynamic body shape to significantly increase top speed. This car driven by Mark Donohue won the 1973 CanAm championship and perhaps best reflects the nickname “Turbo Panzer” that has become synonymous with the 917. In a specially set up run in 1975 the 917/30 set an average speed of 221mph around the Talladega race circuit.